With the weather described simply as ‘not good’, the

Battalion returned to the front line. The two attached companies of the Royal

Scots rendezvoused with the West Ridings at La Rolanderie at 10.45 am. Three of

the eight platoons were assigned to 'shadow' Tunstill’s Men; three more were to work

alongside ‘D’ Company and the other two with ‘B’. For the first two days the officers

and men were to be ‘paired’ on an individual basis at all ranks and then for

the remaining two days they were to be ‘paired’ on a platoon basis. At 5.15 pm

‘A’ Company led the Battalion on their move to the front line, with platoons

marching at intervals of 100 yards and, as they came closer to the front line,

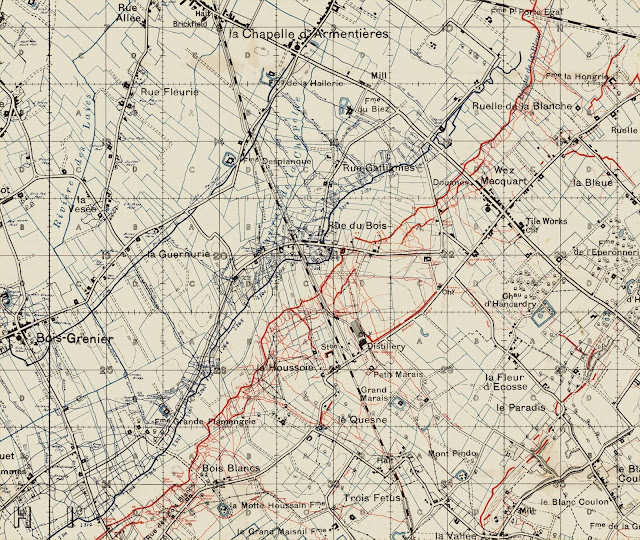

from Gris Pot onwards to Bois Grenier, they proceeded by sections with the men

marching in single file on either side of the road. ‘C’ Company remained in

close reserve in the Bois Grenier Line while the others made their way to the

front line trenches. The Battalion was allocated a 1,000 yard front further south

than on their previous tour, with the right flank at Farm Grande Flamengrie at

the end of the main Shaftesbury Avenue communication trench. This was to be

where Tunstill’s Men were to be positioned, with ‘B’ Company to their immediate

left and ‘D’ further left still. This was familiar ground, which the companies

had occupied on previous tours (see 14th December). The reliefs were completed without incident

by 8 pm. With two extra companies in the line, conditions were more crowded

than usual and company commanders were reminded that, “special note should be

taken of all available dugouts”.

The story of the 16th Royal Scots has been

extensively researched and published in fascinating detail by Jack Alexander in

his excellent book, McCrae’s Battalion,

and extracts from his work help to add detail to the events of the following

days.

Sgt. Gerald Crawford of the Royal Scots wrote to his family

from his billet near Vieux Berquin just before moving up to the line: “for we

have arrived on a salient in the British sector and the noise of guns is now

continuous on all sides. Brother Boche occupies much of the ground to the north

and south, as well as to the east, so we are perfectly besieged”. Having

arrived in the line, Crawford was able to describe his new surroundings, and in

particular his approach to the front line down Shaftesbury Avenue: “The trench

is not wide but the boards are frequently loose so that if your pack makes you

top heavy, or your boots are slippery with mud, you run a fair chance of a dip

in the muddy depths below. Sometimes the enemy may know of your movements, but

if they do not they just keep up an intermittent fire on the off-chance of

catching someone. When you hear the crack of a rifle or the ping of a bullet,

you cannot help ducking your head instinctively at first, but in a few minutes

you get over it. When you finally emerge into the first line trenches you are

again in another world”.

Pte. William Andrew

Leiper Long was admitted via 69th Field Ambulance, 1st

Canadian Casualty Clearing Station and 22nd General Hospital in

Wimereux to 5th Convalescent Depot also in Wimereux; he was

suffering from influenza. He was a 20 year-old weaver from Keighley; he had

enlisted in January 1915 and had been posted to 10DWR in April.

2Lt. John Henry

Hitchin, who had been absent without leave from 11th Battalion

West Ridings for the last month (see 29th

December) checked himself in at the Waterloo Hotel, York Road, Lambeth. He

was wearing the uniform of a Lieutenant and told staff at the hotel that he had

recently been promoted Captain, which, of course, was quite untrue.

A payment of £7 0s 3d, being the amount due on his army pay,

was authorised to John Cardwell, father of Pte. John Cardwell who had been killed two months earlier (see 21st November 1915).

No comments:

Post a Comment